Riding a horse well requires both intuition and command. Equestrians can spend months building a relationship with their animal before even putting on a saddle. With a thousand-pound strong-willed creature, a person must act with certainty and assurance, having a deft yet sensitive hand. Astride her horse, a skilled rider senses her mount’s physical signals and responds quickly and firmly, while trusting their capacity to be as one. A patient process

yields to a leap of faith.

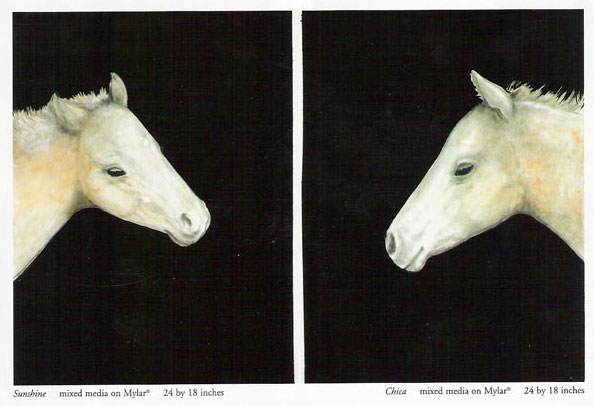

This play of receptivity and control merges opposite impulses into a kind of intelligence rather than habit. The safety of the rider and her horse depend on focus and a knowing response to subtle information and sudden developments. Suzanne Betz brings this proficiency to her art in which intention and accident, order and caprice, hold together in a satisfying equipoise. As both rider and artist, she insists, there is always more to discover. Known for her paintings of horses, Betz places their forms in an ambiguous color field. Removed from a landscape reference, the very placement of the horse implies a conscious choice rather than mere observation. When situated in groups, the horses are arranged in a way that tends toward symmetry while pulling away from it. In a painting of three, Betz pairs two, with one’s head slightly higher, and then the third is spaced at a slight distance with his head shifted to the left. The artist begins with a direct statement or “term” only to “let it move where it needs to be.”

The outlines of the horses are set against a rich black or striking color background resulting in vivid negative spaces. Betz accentuates the push-pull of figure and ground by laying down more than one line: the paint has a boundary that creates one outline, and a rendering line or lines reside within. The juxtaposition of large white forms against stark background is bold, but the point at which they meet is intangible. In speaking of her process, Betz says she doesn’t know when her work will “lurch into something different”: the very phrasing conjures up an animate being’s sudden, unpredictable movement.

Perhaps it is Betz’s uncanny ability to create a presence beyond representation that makes her paintings so appealing. In those lozenge-shaped eyes, the viewer senses some other being. The prominent sculpted nostrils suggest a possible release of breath or snort. Muzzles touching and necks entwined, these horses are sentient beings that appear as curious about as we are about them. Without bridles or restraints, they are self-possessed. Betz finds fascinating, “the energy emitted by a horse.” She crops their bodies so that the viewer stands exhilaratingly close to a creature of both tremendous power and majestic tenderness. Betz weaves this hypnotic moment from few elements. The horse reveals itself from a restrained selection of artful details in which the artist allows her circular forms and her gestures to just be. Color and line intermingle and yet remain independent. In speaking of her spiritual advisor, Betz says, she learned that helping the world meant being lighter upon it. In her painting, the artist employs this simplicity and nimbleness like reins held loosely across the palm of one’s hand, while still conveying the sense of life force there. Although the horse may be her subject, Betz’s involvement with her materials adds another dimension. By embracing the physical substance of her processes, Betz can refer beyond to express the metaphysical. The artist experiments with paints and surfaces, never using materials traditionally. The emergence of a painting may be an exchange of adding and subtracting, in which Betz balances illusion and transparency. In this sense the artist finds a comparison of her methods with life itself as “looking through one thing and seeing something else.”

Most distinctive is the luminosity that the artist achieves. Rather than a flat area of color or a sequence of strokes, the horses and the painting almost radiate light. Betz contrasts white with black, and she pushes the on-off relationship by using an unexpected color as a void. Instead of finding themselves at odds, one tone supports and enhances the other with electrifying effect.

The artist has recently begun a series of paintings with bright or rich colors in which horses sometimes seem as if they are suspended in the air. Our visceral understanding of a horse’s weight is countered by the ethereal quality that Betz imparts. She renders the legs in a manner that suggests that the horses have lost contact with the ground, and they seem to rise and float in a kind of ascension. The addition of a ladderlike form also underscores the disorientation of above/below or up/down. With this open frame of reference, Betz allows for possibilities as even the orange field ambiguously suggests both earth and sky. At the same time that she enhances the otherworldly aspect of her horses, Betz takes a turn to the fundamental element of drawing. She uses line as an exploration of the multiple aspects of the horse even those not typically seen from a normal vantage point. Her hand creates marks that define as well as traces that act independently and expressively. Through one, the viewer senses a slow, regular gliding; through the other, a muscular rhythm. Just as the rider maintains stability, Betz holds to her own inner core while extending her expressive reach, a constant balancing of opposing forces.

In the repetition of the horse as subject, the artist persists in questioning what the act of making can be. Betz is transfixed by the unfolding of the process and is engaged with the endless variety available. “If I do this, what will happen?” is the impulse that pushes her. In her use of materials, Betz is less concerned with how something works than with what something will do: What mark will it make? What effect will it have? In the creative flow, she lets go of the conscious mind so that objects, such as a ladder or a hand, emerge in her imagery, more a

prefigurative sign than a preconceived idea.

Just as Betz engages her materials and her process, so then does the finished painting become a stimulus for the viewer’s own response. Through directness and intensity, viewers are invited to connect and to imagine. Indeed, the artist wishes not to reveal too much about herself or her working methods lest it impose upon the viewer’s individual emotion and unfettered interpretation. Yet the fearlessness and honesty of her gestures is an invitation to release.

With such economy of means, Betz’s horses tap into a deep wellspring of emotion and embody an ancient primal connection. Those with an understanding of horses appreciate her discernment and respect for the character of the animal. Never a portrait, her equine figures emerge from an intimate knowledge and identification that accommodates an individual’s recognition of a beloved mare or stallion. Even those who only know horses from a distance relate to the animal’s spirit or to the revelation of that essence within themselves. Betz returns us to the first human encounter with that one horse that allowed us to come within reach – and moved us beyond our own limitations.

(Article written by Stephanie Grilli, Ph.D. art history, Yale)

![]()